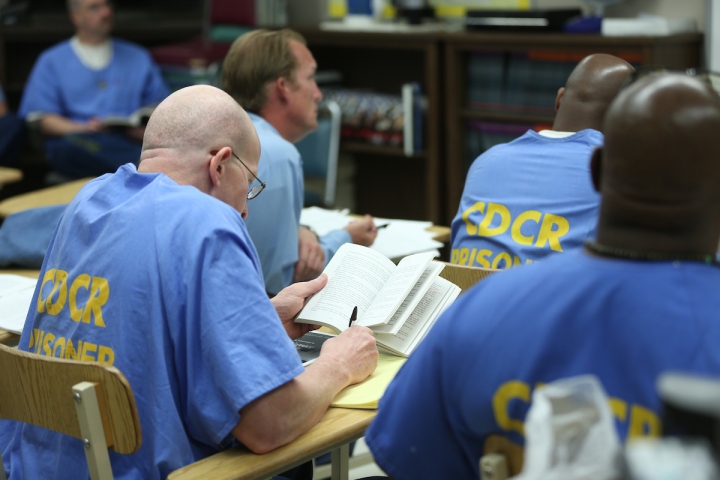

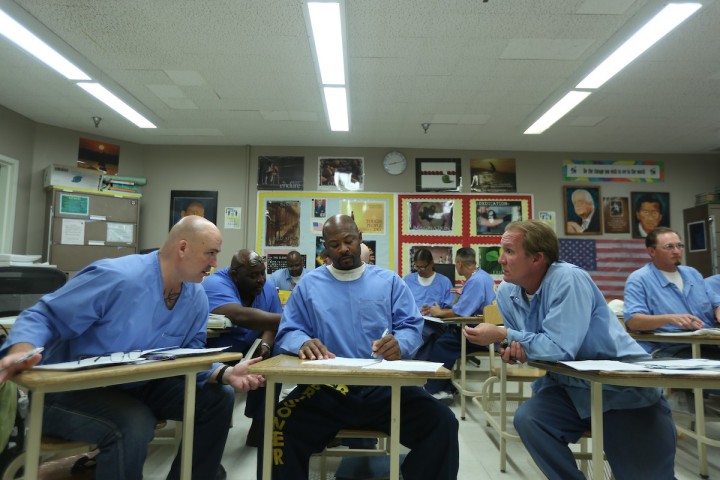

Those of us who have been running prison education programs for awhile know it is up to the Warden to decide what programs will be offered. Yet, while the Warden sets the educational policy and priorities for the institution, we also know that it is the correctional officers (once less respectfully referred to as “guards”) who can make or break a program. Without the support of the guards, all kinds of weird little things can go wrong. Faculty members could be left in waiting rooms for hours. Students could be kept locked in their cells instead of escorted to the classroom. Computers might be broken or mysteriously stop working. Books could be taken away. Important papers and documents get “lost” in the mail. Working in the prison environment has brought me face to face with powerful, “street level bureaucrats” who impact public policy every day (Cooper, et al. 2015).

***

December 6, 2016.

TO: Chief Deputy Warden, CSP-Los Angeles County

Dear Chief Deputy Warden:

I’m writing to request your help on a matter of utmost seriousness. I’m sorry to say, ma’am, but the retaliation has not ceased, but instead, has now increased to include a few more officers, with the nature of the attacks (harassments) becoming more physiologically and psychologically dangerous. I’m truly convinced that these harassing attacks will NOT stop until Sergeant W utterly destroys me personally or decimates my rehabilitative efforts to become a positive human being. Therefore, I am please asking you to transfer me out….I tried my best to endure it so that I could continue with Cal State LA and the rest of my positive programming. …. I just want to leave this bad situation while it is still safe for me to do so, so that I can continue my rehabilitative efforts elsewhere.

Sincerely,

K.P. – Cal State LA Student

***

In Street-level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services (2010), Michael Lipsky contends that “Street-level bureacrats may consider legitimate the right of managers to provide directives, but they may consider their managers’ policy objectives illegitimate.” I see these dynamics between prison administrators and front line correctional officers all the time.

It is not as bad as it used to be, but K.P. was certainly not the only incarcerated student of ours who was harassed and made to feel inferior for pursuing an education. Confronting the correctional officers put me on iffy-ground — to be appear argumentative would have most certainly caused a backlash and disservice to the program. To be too deferential, however, would appear weak and acquiescent. And most importantly, to take my complaints directly up the ladder to the Warden would have signaled war.

In hindsight, I recognize that the Warden made a huge mistake when he alone green-lighted Cal State LA’s BA degree program at the prison. Rippner stresses the importance of involving stakeholders throughout the four stages of policy development however at the prison, there was never a time that the correctional officers were actually informed – much less consulted – about starting a college education program at the facility. Instead, one bright day, a couple of college professors showed up at the gate bearing books and syllabi and a cheery demeanor that was met with skepticism and derision from almost every correctional officer.

Lipsky writes:

When relationships between policy deliverers and managers are conflictual and reciprocal, policy implementation analysis must question assumptions that influence flows with authority from higher to lower levels, and that there is an intrinsic shared interest to achieving agency objectives. This situation requires analysis that starts from an understanding of the working conditions and priorities of those who deliver policy and the limits on circumscribing those jobs by recombining conventional sanctions and incentives. (2010, pg. 25).

Now, a few years into the program, correctional officers have mostly stopped blatant attempts to derail the program. Some CO’s welcome working on a yard that emphasizes education because there is less violence and fewer behavior challenges. Still, many of the guards are philosophically against providing an education to prisoners and they resent the expectations and work that have been imposed upon them. Correctional officers have a long history of serving as street-level bureaucrats and that is no less true at the prison I work in. However, had we followed Rippner’s advice and included the correctional officers in the early information gathering and planning phases, I suspect we probably would have had a smoother roll-out. Consider it lessons learned!

References

Cooper, M. J., Sornalingam, S., & O’Donnell, C. (2015). Street-level bureaucracy: an underused theoretical model for general practice? The British Journal of General Practice, 65(636), 376–377. http://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp15X685921

Lipsky, M. (2010 originally published in 1980). Street-Level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. Russel Sage, New York.

P, K. (2016). Lancaster BA Program [Letter to Chief Deputy Warden]. Lancaster, CA.

Rippner, J. (2016). The American education policy landscape.